Malta-Shining light in Darkness

CR- Good article from NOR, read and enjoy. Anyone with immigrating information and job info, let me know.

(flag of Malta)

Contrasts in Christendom: Red Lights in Amsterdam, Neon In Malta

October 2006By Thomas Basil

Thomas Basil entered the Catholic Church in 1996. He resides in the Archdiocese of Baltimore with his wife and six children.

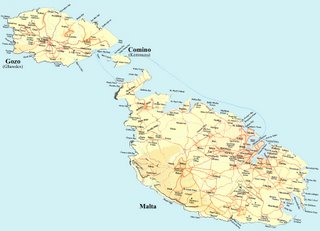

It is sunset in Bugibba. Small tourist hotels and shops crowd a Mediterranean boulevard teeming with holiday-minded Europeans. Most are surely unaware that their vacation spot ranks a full chapter in the New Testament, Acts 28. In A.D. 60 a shipwreck here changed this island forever. The Church of St. Paul's Bonfire now stands in the boulevard's median strip. Here a serpent tried to strike down the Apostle Paul after he was cast ashore on Malta.

Malta is a remnant speck of Christendom off the coast of a post-Christian western Europe. Malta is home to 365 Catholic churches, roughly one for every 1,000 residents. Of her 400,000 citizens, 98 percent profess Catholicism and, more significantly, 85 percent attend Sunday Mass. The national flag is the feudal eight-point Maltese cross. Malta's state university trains future doctors and engineers as well as future priests. Public schools teach Catholicism as a required subject. Political debate is not over a woman's "right" to abort, but over a couple's "right" to divorce. Malta quaintly outlaws both modern liberties.

Before arriving in Malta, my itinerary took me to Amsterdam, where liberties flourish. In her Red Light district, prostitutes in underwear pose in storefront windows in shops directly opposite an obsolete medieval cathedral. Paid by credit card, prostitutes ply their trade shielded from onlookers only by a curtain pulled across their street-level window. Their professional status is secured by a Dutch labor union for "sex workers." Other Amsterdam sights included its airport's "meditation center," which holds a Sunday "multi-religious" service in a "chapel" devoid of any cross, but with a large arrow on the floor showing the direction to pray toward Mecca; and the suburban Amsterdam parish near my hotel where an elderly nun tallied Mass attendance for me as "about 15 on Saturday night; on Sunday about 100.

"Malta's equivalent to Amsterdam's Red Light district is an area known as Paceville. It too is jammed with passersby in search of a good time. But absent are store windows crammed with either prostitutes or obscene sex toys. Instead, its stores include souvenir statues of St. Padre Pio and ceramics of famous Maltese churches. Paceville's most provocative storefront has shelves filled with penis enlargement, breast enhancement, and other hedonistic potions. A neon sign blazes the shop's name: "Made in America."

Malta's Paceville is probably the world's only nightclub zone with a Eucharistic Adoration chapel. Founded by an Augustinian priest named Fr. Hillary, it is called The Millennium Chapel. The chapel's exterior mixes a multi-colored neon sign reading "WOW -- Wishing Others Well," a bronze sign of St. Augustine's famous quote, "Our hearts are restless O Lord until they rest in thee," and statuary of a pregnant woman, a weary businessman, an alcoholic, and a rebellious child at the door. Inside you meet the risen Christ painted in a rainbow of pastels on a triangular canvas. From the aqua-colored monstrance to the background music of waterfalls and birds, the chapel is a rare thing in Malta, an architecturally modernist church.

Open until 2 AM nightly, the Millennium Chapel hosts a 9:30 PM Saturday night Mass for the party crowd, plus a bookstore, a game room, a food pantry, counseling rooms, and a television lounge. A volunteer staff of 100 runs it all. During my visits I always saw young Maltese taking a break from the nightlife, many kneeling before the Blessed Sacrament, behind which the scheduled adorers of an older generation kept watch. It is a remarkable sight.

Many public transit buses in Malta lack doors, and nothing keeps the unsteady passenger from tumbling out except the watchful eye of God, seen in ceramic figurines of Jesus and Mary above the driver. Prayer cards of the Sacred and Immaculate Hearts, or a banner reading "Trust in God," adorned other buses but did not prevent drivers from cheating me more than once with too little change in the unfamiliar Maltese lira.

The hand of Providence seems to have guided not only Malta's bus system, but its very geography as well. Not far beyond where St. Paul shipwrecked begins a coastline of sheer cliffs. Had he hit land slightly west, there would have been no survivors. In the capital city of Valetta is the Church of St. Paul Shipwrecked, which depicts in sumptuous baroque murals every event of his life from the Bible. On the feast day of the shipwreck, February 10, its larger-than-life statue of St. Paul preaching is processed through city streets. The statue also was processed in 1798 in divine supplication as Napoleon's invasion fleet approached, and in 1960, when Malta celebrated the 1,900-year anniversary of St. Paul's arrival.

On one altar is enthroned a silver forearm encasing bones from the Apostle's hand. Ancient wax-sealed parchments allege its authenticity. Another altar holds a three-foot-high marble pillar topped by a silver sculpture of a severed head. It was on this pillar that St. Paul was beheaded. In 1818 Pope Pius VII bequeathed it to the Shipwreck Church in gratitude for parishioners' heroic service during an outbreak of the plague.

It is worth comparing the state of Christendom circa 1818 in the lands cleansed of relics by the Reformation. Lutheranism in German seminaries was hot with higher criticism claiming the Bible was unhistorical mythology. Anglicanism in Britain was beginning its theological drift that in a mere two centuries crowned an openly homosexual bishop in the U.S. Calvinism in New England had replaced Christ with Unitarianism. Yet in Maltese Catholicism circa 1818, New Testament relics were showcased in churches that portrayed New Testament stories as both spiritual and historical realities.

Valetta has 38 churches within its walls. Thirty-seven are Catholic. One is an Episcopal cathedral left over from British rule; nearest that altar are inscribed not saints' names but those of British ships that kept Malta supplied during the Nazi siege of World War II and a sort of relic -- a letter from England's Queen Mother. It was a visible reminder that non-Catholic churches typically trace back to a single nationality, and lack a trans-cultural broadness.

The most prominent Christians in Maltese history after St. Paul are the religious order today known as the Knights of Malta, founded in 1070 as the Sovereign and Military Order of the Knights Hospitaller of St. John of Jerusalem. It is the fourth oldest religious order still extant in the Catholic Church. Its motto has remained unaltered since 1099, Tuitio Fidei et Obsequium Pauperum -- "to defend the faith and to serve the poor."

The Knights initial role of hospitals for Catholic pilgrims evolved into military functions during conflicts with Islam, and the Knights became a strong fighting force. The Order was composed of hereditary noblemen from all portions of Europe. Its Grand Master might hail from Portugal, Germany, Spain, Italy, or England, although most were in fact French.

The Knights quit Jerusalem in 1291 when Islam conquered. They next took the Greek island of Rhodes as headquarters, and rebuffed four major Moslem assaults until a six-month siege in 1522, when they surrendered on Christmas Eve to Turkish Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent, who allowed survivor Knights to depart unmolested. In 1530 Holy Roman Emperor Charles V bequeathed Malta to the Knights as their new naval homeport, their navy then being one of the best in the world.

The Knight's worst defeat came not from Islam but from the French Revolution, which confiscated the income of their French estates, and whose Napoleonic fleet ignored the Knights' neutrality and seized Malta in 1798. The Knights reconstituted in 1834 as a Catholic charitable society. Membership today consists of 11,000 Knights and Dames living in 54 nations. The Order maintains diplomatic relations with over 90 nations and has permanent observer status at the United Nations. Its territory consists of one building in Rome. It is something akin to the Red Cross, as it runs hospitals; and somewhat akin to a nation, in that uniformed peacekeeper Knights serve in Bosnia. As for Malta, the British occupied the island in 1803, dallied with returning it to the Knights, but instead made it a colony until granting independence in 1964.

The Knights' noblest moment came during what is still known as the Great Siege of Malta. In 1565 the Turkish Sultan besieged Malta with a fleet of 373 vessels and 40,000 men. Opposing him were a meager 500 Knights, 400 Spanish troops, and 4,000 Maltese men. Despite the hopeless odds, 70-year-old Grand Master Knight Jean Parisot de La Valette outwitted the Sultan's commanders and forced a Turkish retreat. At one point all captive Christians were decapitated by the Moslem commander, their heads displayed on pikes, and their corpses nailed to crosses sent to drift across the harbor to La Valette's fortress. La Valette retaliated immediately by executing all Moslem prisoners and using their severed heads as canon shot. Today Malta's capital city bears La Valette's name.

One guesses that the religious antipathy remains. Despite its position off the north African coast, there were no mosques in Malta until the 1980s, when one -- and only one -- was allowed to open. Unlike the rest of western Europe, one sees almost no Moslem women out on the street, at least none identifiable by the wearing of headscarves. Only 2.2 percent of the populace is immigrant, the lowest proportion of any western European nation. Malta's old capital of Mdina, which bears the name of the first Arabian city ruled by Mohammed, is the only city so named outside of the Moslem world. Yet in the Maltese Mdina there are found only churches, no mosques.

Malta seems overflowing with Catholicism to a visitor from the secularized West. Each village has an annual festival on the feast of its patron saint, and seemingly not just for tourists. Half of all homes seem to have a ceramic Madonna and Child or Sacred Heart of Jesus embedded into their exterior front walls. Midway through a highway tunnel in Valetta, I find a chapel! In this man-made cave is an altar jammed with statues, icons, lights, and votive candles, which are sold in local grocery stores. On a cliff overlooking the tunnel exit is a similar chapel. On open land in the countryside is a life-size status of Joseph and the Infant Jesus, brightly lit. In the center of one traffic circle sits a tiny chapel. In the center of another, a town cross of recent origins. Built into the side of a modern warehouse is a niche holding a statue of the Blessed Virgin.

I'm told that upkeep of each of these shrines is by a local family, a local business, or the municipal government. During my week in Malta I never once saw a shrine that appeared abandoned or in ruins, but I did see a large and spanking new crucifix on the wall behind the hotel reception desk. At my hotel I found on television what I'd never seen elsewhere in Europe: Mother Angelica's EWTN, and unusually enough for modern hotels, no pornography. At five weekday Masses at Fr. Hillary's church I find the pews full. Mass and prayers are said in Maltese, a linguistic descendant of ancient Phoenician.

Malta's Catholicism is obviously not unshaken by postmodern culture. The glossy Malta Economic Update magazine is full of congratulatory stories on women who'd set aside childbearing in favor of business careers. Malta's families now average under two children apiece. Vocations are similarly depopulated. The Carmelite church in Valetta had 38 priests after World War II. Today it has three. The Augustinian church in Paceville once had seven friars, but now has two active and one retired.

Nevertheless, Malta's Catholicism seems still capable of cultural fight. In 2002 the Dutch abortion group Women on Waves sailed its floating abortion clinic, the Aurora, toward Malta. The government declared that anyone who assisted the ship was committing a criminal act, and, I was told, dispatched Navy vessels to chase it away. Intriguingly, the Aurora's website celebrates its trips to Poland and Ireland, but gives no report on the outcome of its Malta trip.

When Malta joined the European Union in 2004, it did so only after signing a protocol exempting its abortion laws from EU jurisdiction. Later that year, a UN committee suggested Malta legalize abortion in "extreme" cases. Malta's three bishops retorted that "abortion is and remains the murder of innocent persons, whatever the reason behind it," and the island remains safe for unborn babies.

In Malta I visited the Chapel of Our Lady's Return from Egypt. It is located on Malta's offshore island of Comino, which spans 743 acres uninhabited except for one farmhouse, two small hotels, and the chapel. The island has banned all automobiles. A tourist boat took me to Comino's famous Blue Lagoon of clear aqua seas and watery caves under its coastal cliffs. These provided a spectacular movie set for The Count of Monte Cristo, starring the soon-to-be famous Jim Caviezel, who later portrayed Jesus in Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ. But what impressed me most came later while wandering ashore. I chanced upon a secluded cove, near which stood a tiny church of windowless earthen walls topped by a triple belfry. Tacked to the door was an index card with a handwritten note reading: "Masses: Saturday 5:30, Sunday 9:30." I learned that a priest arrives here by boat every weekend to celebrate Mass.

In Amsterdam from 1581 to 1785 it was illegal for any church building to be used for Catholic worship, although Catholicism remained legal in private residences as long as it was invisible from the street. In 1661 Dutch merchant Jan Hartman converted the upper floors of his canal-front home into an ornate chapel seating 150 persons, complete with organ. Today, Hartman's house is a museum to Catholicism named "Our Lord in the Attic." It is in the middle of the Red Light district of Amsterdam. Prostitutes waved and smiled at me as I walked there midday along streets once home to public Eucharistic processions in which even the Holy Roman Emperor walked.

In Holland history has kept Catholicism in the attic for centuries. In Malta history has kept Catholicism alive, even on uninhabited islands. I think this explains more than a few of the differences I observed. Historian Hilaire Belloc once wrote that in "The re-conversion of our world to the Catholic standpoint lies the only hope for the future [of Western civilization]." Maybe I saw hope for such cultural renewal even in the heart of post-Christian Europe.

Near the Red Light district of Amsterdam, a 19th-century church stands open during the day, guarded by two ushers in suit and tie. During my visit, one rushed up the center aisle to confront a teenager kneeling at the altar rail. Urgent words were spoken, the boy removed his baseball cap, and the usher retreated. By such small steps is Western civilization renewed. Take note that the restoration began in a Catholic church.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home